By Don Wilson

The 24/7 Health & 9-5 Safety Professional

I was invited to deliver the keynote address at a health and safety leadership conference on the topic of reducing serious injuries and fatalities (SIFs).

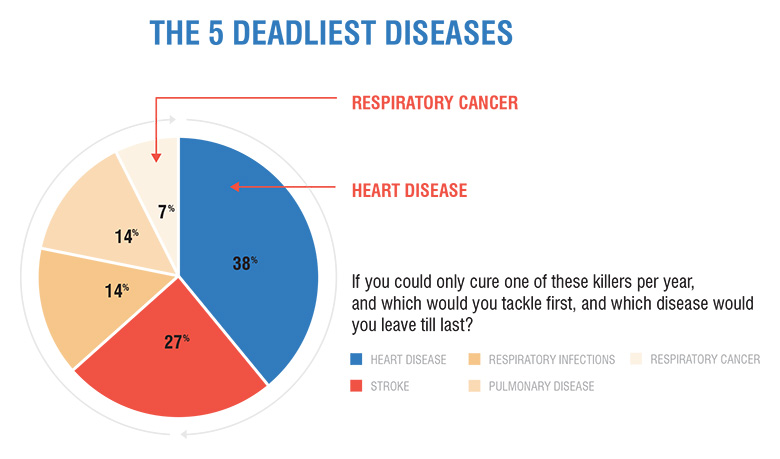

The audience was made up of global health and safety leaders who represented diverse organizations from across North America and around the world. Before starting the discussion on possible approaches to SIF reduction, I asked the group how they would approach the problem if the topic we were looking into was not reducing fatal injuries but instead was reducing fatal illnesses. I showed the group a diagram showing the five deadliest diseases, according to the World Health Organization.

I asked the group to consider this question: “If you managed a global medical research team that had the personnel, skills and resources to eliminate one of these diseases per year, which disease would you tackle first, and which disease would you leave till last?”

They overwhelmingly indicated heart disease as the first priority and respiratory cancer as the last priority. Their reasoning was both obvious and intuitive. Since heart disease kills over five times more people than respiratory cancer every year, the ethical choice is to concentrate the limited resources available on it first and save the most lives possible. Their approach to solving this hypothetical scenario is consistent with the approach these same professionals take in the real world with the health of their employees. All health issues in their safety-and-health responsibilities are approached and prioritized as 24/7 problems.

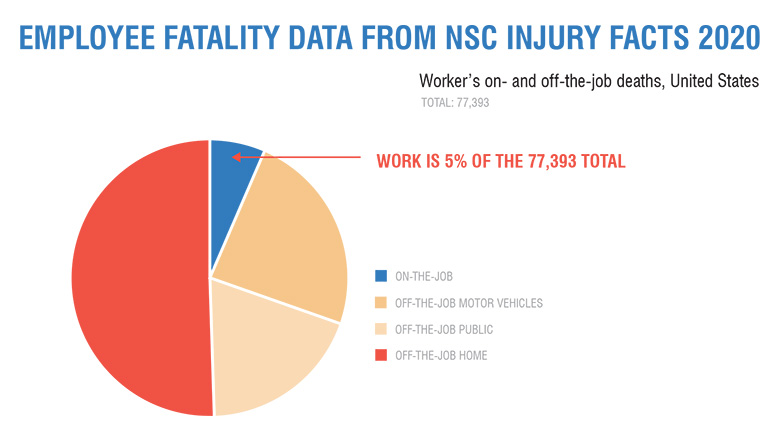

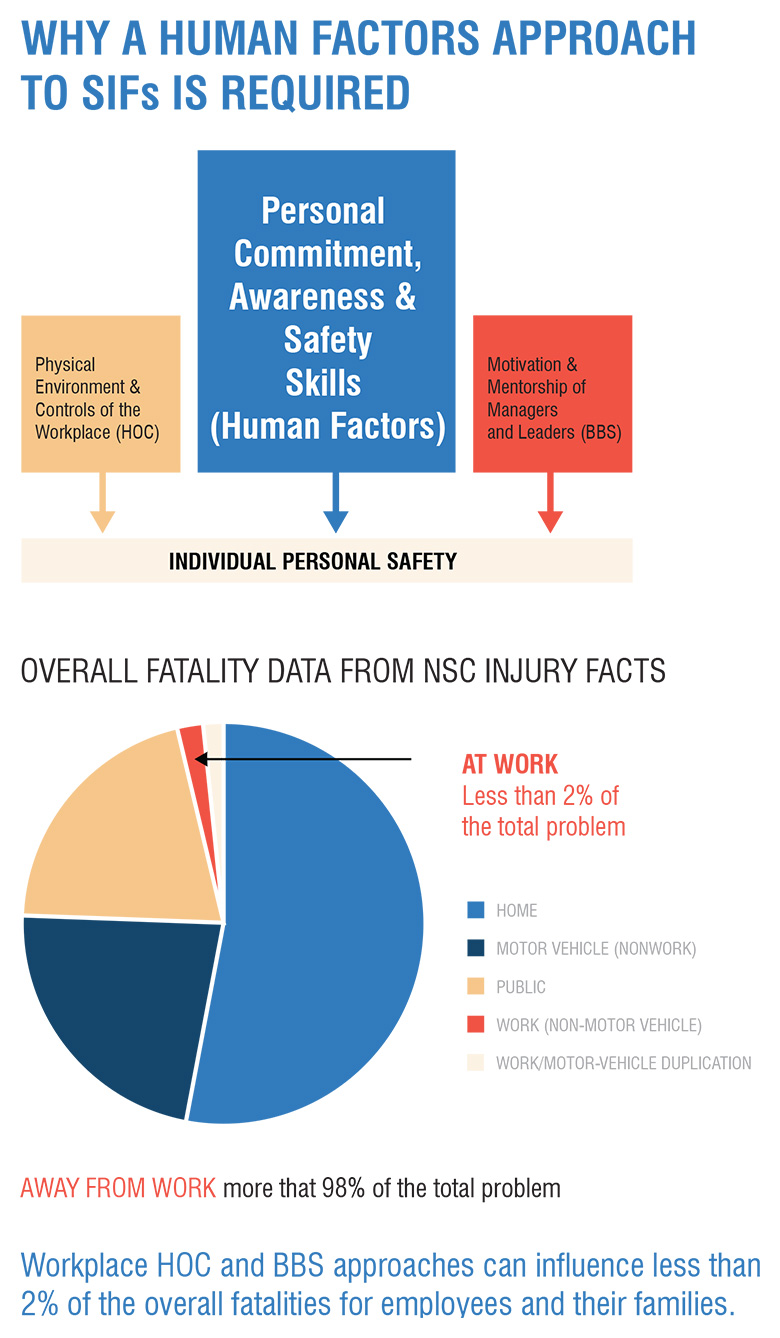

Having established the group’s consensus on a 24/7 approach to employee health issues, I then turned the conversation back to the original topic—reducing serious injuries and fatalities (SIFs). I showed the group the National Safety Council’s summary data on employee fatalities.

I then asked the group, “Since most of you here today lead a global safety team that has personnel, skills and resources to reduce serious injuries and fatalities, what is the ethical approach to this 24/7 problem?” From the standpoint of reducing SIFs, almost all of their organization’s time, money and resources are applied to the area least likely to cause serious injuries or fatalities to their employees, even though their CEO routinely refers to workers as “this organization’s most valuable asset.” You can probably imagine the scene I witnessed from the podium—a room full of people shifting uncomfortably in their chairs as they reflected on the inconsistency of the approach most of them take to employee health versus employee safety.

I spend a great deal of time thinking and talking about why employee health is treated like a 24/7 issue but safety is only a 9-to-5 problem. Part of the answer lies in the traditional mindset and approaches to workplace safety developed through our experience of conditions as they existed in the past. The factories and mills that previous generations worked in were the biggest places of danger in people’s lives. The most efficient way to deal with this danger was to systematically eliminate the hazards in these closed and rarely changing working environments. The hierarchy of controls became the gold standard for reducing SIFs in workplaces. After all, if you can eliminate a hazard (and new hazards rarely arise), most injuries and fatalities can be eliminated through rigorous and reliable engineering controls.

While the hierarchy of controls went a long way towards dramatically improving safety in workplaces, pioneers in organizational safety leadership realized that this approach by itself wasn’t enough to completely eliminate workplace injuries and fatalities because humans are, unfortunately, only human—which is to say that our behavior is variable. We make unintentional mistakes and poor choices, fail to communicate risks, misjudge, are overconfident in our abilities, get tired, and forget crucial safety procedures.

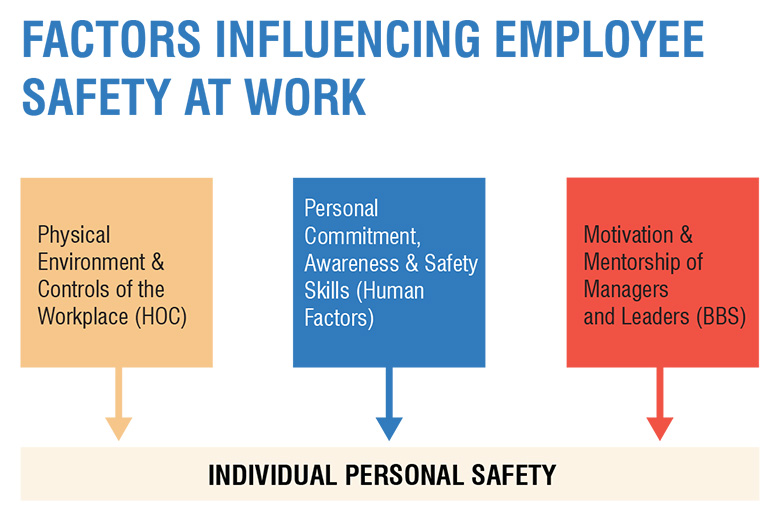

To combat these human limitations, additional systems that augmented the hierarchy of controls were added through existing workplace employee oversight systems. The day-to-day management activities of leaders, managers and supervisors were revised to include safety mentorship, coaching and motivation. Inspired by lean manufacturing practices, employees on the shop floor were tasked with providing direct input into efforts to improve, and were expected to take more ownership and personal responsibility for overall workplace safety. The present three-prong approach to workplace safety management can be visualized as three areas of influence.

Over time, there have been advancements in workplace safety tools, systems and approaches that have led to dramatic improvements to workplace safety outcomes (and this important work will need to continue). Unfortunately, at the same time, the law of diminishing returns has begun to rear its ugly head. There is very little low-hanging fruit that most world-class organizations can harvest in their workplaces to reduce SIFs further.

Over time, there have been advancements in workplace safety tools, systems and approaches that have led to dramatic improvements to workplace safety outcomes (and this important work will need to continue). Unfortunately, at the same time, the law of diminishing returns has begun to rear its ugly head. There is very little low-hanging fruit that most world-class organizations can harvest in their workplaces to reduce SIFs further.

So where does low-hanging fruit still exist for SIF reduction? It is clear from the NSC aggregate data that modern workplaces are no longer the most dangerous places in our lives. In fact, they’re now the safest—far safer than our homes, public spaces and roads. We are now at the point where, for most organizations, reducing fatalities that occur outside of work by only 5% would save more employee lives than reducing all future workplace fatalities to zero!

The essential question that health and safety professionals should ask themselves is: “Do I care about reducing all fatalities for our employees or do I only want to reduce the very small number of workplace fatalities?” The answer to this question is obvious—it’s time to take the same 24/7 approach to employee safety as we have always had for employee health.

So how can we reduce SIFs and improve safety for our employees outside the workplace in the same way that we have on the job? What tools and systems will work 24/7? One obvious but extremely important consideration is that, as we try to improve safety everywhere, we are moving from a command-and-control environment to other places in our employees’ lives where we have influence only. It’s not like your organization’s managers and supervisors are following your employees as they drive home at the end of their shift to police their compliance with driving rules and regulations or to audit proper roadside guardrail placement.

So how can we reduce SIFs and improve safety for our employees outside the workplace in the same way that we have on the job? What tools and systems will work 24/7? One obvious but extremely important consideration is that, as we try to improve safety everywhere, we are moving from a command-and-control environment to other places in our employees’ lives where we have influence only. It’s not like your organization’s managers and supervisors are following your employees as they drive home at the end of their shift to police their compliance with driving rules and regulations or to audit proper roadside guardrail placement.

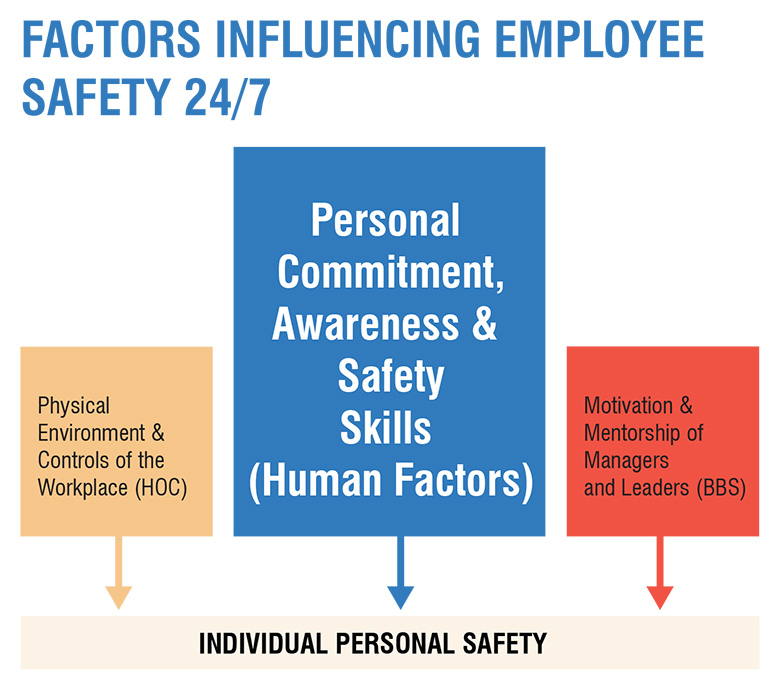

As we move to a 24/7 approach, we lose almost all of our ability to control the hazards our employees encounter in different environments each day. When our employees drive to work in the morning, we can’t make other drivers on the road pull over and park so our workers can commute hazard free. If we re-examine the three areas of influence used in the workplace to reduce SIFs, we see that their effectiveness changes dramatically as we strive to reduce injuries and fatalities 24/7.

It quickly becomes clear that influencing motivation and ability in the personal area has by far the greatest potential for reducing SIFs everywhere. This is because the individual is the only “system component” that is universally present in every situation. Individuals are the only ones who can exert some measure of control on themselves at all times.

It quickly becomes clear that influencing motivation and ability in the personal area has by far the greatest potential for reducing SIFs everywhere. This is because the individual is the only “system component” that is universally present in every situation. Individuals are the only ones who can exert some measure of control on themselves at all times.

But the tools and systems routinely used in the workplace to influence individual safety awareness and skills are almost never voluntarily used by employees when they are off the job. The H&S leaders laughed when I asked them how much money they would be willing to bet that if we dropped in on an employee at home, we would find any of the following commonplace workplace safety systems in regular use:

- Adults routinely performing a job safety analysis before cooking supper.

- The family conducting a thorough root cause analysis whenever someone is hurt.

- Written procedures posted in the garage and reviewed before using power tools.

- Pre-use checklist paperwork filled out and filed before using lawn mowers, tractors and trimmers.

- Both spouses routinely conducting safety observations on each other and their children based on an organized schedule, with leading indicator metric reports distributed and discussed around the dinner table.

The problem is that these command-and-control workplace systems and tools don’t meet any of the influence-only criteria required for voluntary 24/7 use. Substantial rates of adoption will only ever occur when personal safety skills and tools meet three fundamental criteria:

- They are portable for 24/7 use.

- They are easy and flexible to use.

- Individuals perceive them as valuable.

How flexible and portable are traditional workplace and safety tools? Most aren’t at all.

24/7 SIF Reduction and the Pareto principle

So how do we most effectively reduce SIFs 24/7? One important rule to keep in mind when trying to resolve a complex problem with a lot of variables and moving parts is the Pareto principle (sometimes referred to as the 80/20 rule, which states that a very small number of causes almost always leads to the vast majority of outcomes or effects).

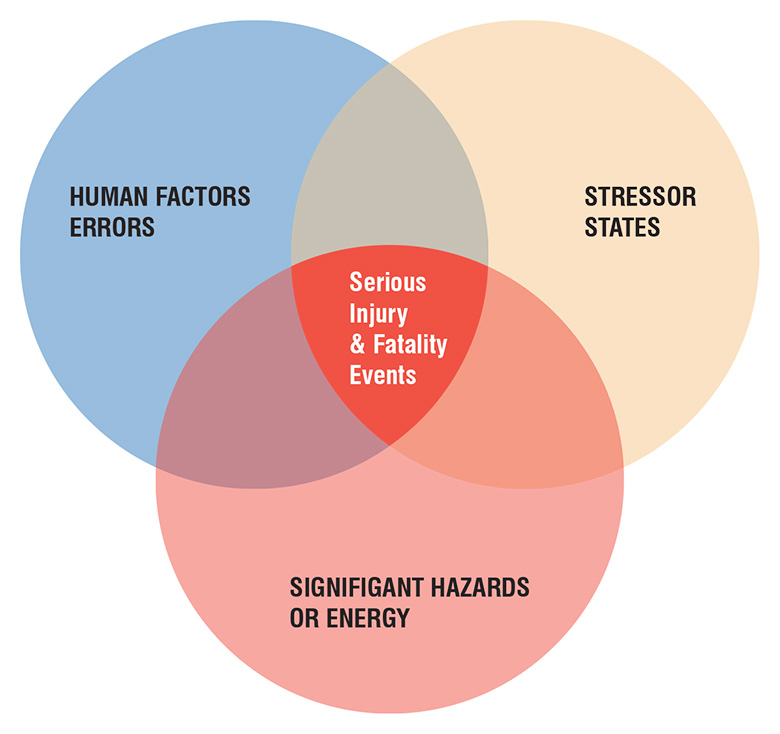

The good news is that most injury events are not primarily caused by a lack of knowledge about the hazards involved or the procedures for dealing with them. Most people know that falling off the roof while cleaning the eaves will likely mean a trip to the ER, just as most people know that stepping off the curb in front of a bus will cause some serious health concerns. Most 24/7 injury events involve familiar hazards and adhere to the Pareto principle in that they:

- Usually follow a simple, regular and consistent pattern of unintentional human factor errors (like getting caught in the line of fire of the moving bus while looking at your cell phone, or slipping and falling on a flight of stairs)

- Almost always occur when a stressor state (like frustration or fatigue) is negatively affecting the individual involved.

SIF events follow these two general rules, but they differ from other incidents in that they only occur when significant hazards or hazardous energy potential are also present (which is one reason that so many fatalities involve motor vehicles and falls from height—the kinetic and gravitational energy can be tremendous).

If people often know about the hazard or hazardous energy that can injure them, why do they still make contact with it? Unintentional human error is almost always in the mix somewhere, and most serious injuries caused by known hazards occur when an individual mistakenly:

If people often know about the hazard or hazardous energy that can injure them, why do they still make contact with it? Unintentional human error is almost always in the mix somewhere, and most serious injuries caused by known hazards occur when an individual mistakenly:

- takes their eyes off the hazard (and loses the reflexive ability to avoid contact)

- stops thinking about the hazard (and does not process the possible sequence of events that could lead to contact and injury)

- puts themselves in the path of hazardous energy (like stepping off the curb in front of the bus)

- loses their balance, traction or grip (and gravity or kinetic energy moves them into contact with the hazard)

At this point, it’s worth asking what causes people to make these unintentional errors. After all, no one likes to get hurt or wants to deal with the immediate consequence of pain and suffering. But it’s not just safety mistakes that have undesired outcomes. Almost every unintentional error we make has some resultant negative consequences. If we can take a Pareto approach to determine a few causes of the majority of errors, then we may be able to uncover some common causes of most workplace injuries. So a more apt question to ask is: Why do people make all forms of unintentional errors (including the small subset of safety and SIF errors)?

Inducing and Avoiding Human Factor Errors

A good place to start is with people who actually need other people to make mistakes in order to accomplish their goals. This requirement arises in almost all competitive situations involving two parties and is routinely demonstrated in team sports. In zero-sum situations, one side’s loss becomes the other side’s gain, so inducing opposition mistakes is built into the strategy employed by players, coaches and managers. If you have ever watched a professional game of almost any kind, you have seen firsthand that any unintentional mistakes by opposing team results in a benefit for your side (and visa versa). What you might not have noticed is that both sides purposefully try to induce stressor states in members of the opposing squad while actively trying to restrict the development of these same states in their own players:

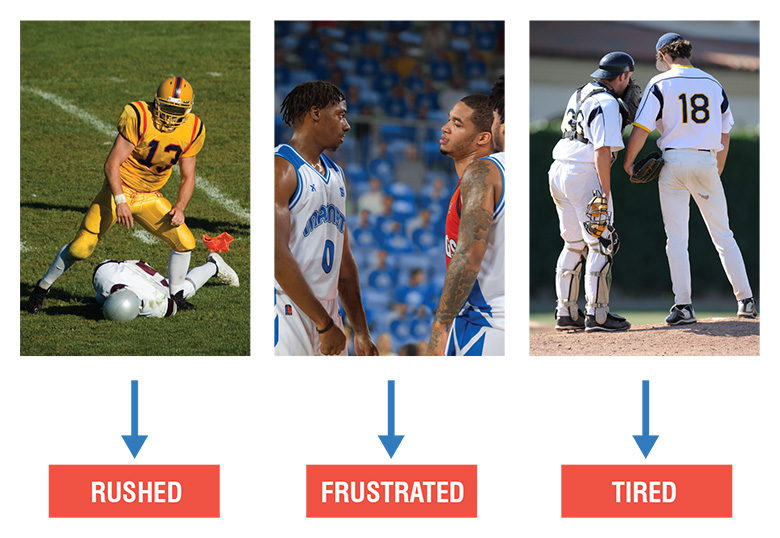

- In American football, the defence rushes the quarterback, hoping the result is more interceptions, incompletions and fumbles. Fighting fire with fire, the offence routinely employs a no-huddle hurry-up system that induces rushing and, over the course of the game, fatigue in the opposition defensive players.

- In basketball and soccer, individual players deliberately induce the stressor state of frustration by taunting, hacking and fouling members of the opposition team.

- Baseball managers closely monitor the number of balls thrown by their own pitchers on the mound as they know this is a leading indicator metric for the stressor state of fatigue that leads to opposing runs scored (a quality problem).

- The playbooks of almost all coaches and managers include trick plays that exploit complacency and lack of focus.

This dual management approach is used deliberately and methodically in almost every competitive sport played around the globe because literally millions of hours of actual experience have demonstrated its effectiveness—the side that reliably makes fewer mistakes (by inducing and avoiding stressors) during each game usually wins.

Whenever the environment is zero sum, the same deliberate inducement of stressors is always employed. Familiar non-sports examples include:

Whenever the environment is zero sum, the same deliberate inducement of stressors is always employed. Familiar non-sports examples include:

- Trial lawyers badgering opposition witnesses on the stand to expose inconsistencies in their testimony (inducing the error-causing stressors of rushing and frustration)

- Military commanders using strategies like lulling the opposing army into a false sense of security by ceasing all attacks for an extended period of time and then surprising the now-complacent enemy with overwhelming force (the stressor of complacency followed by the stressors of rushing and panic).

- Police interrogators routinely making suspects spend long periods of time in cramped and hot interrogation rooms in hopes that wearing them down will cause a confession to slip out (employing both physical and mental fatigue stressors).

Wherever competitive situations arise, people have learned that a small, consistent set of physical and mental stressors have shown themselves to be reliable and effective tools for getting people to make mistakes. And this same small, consistent set of stressors also arise in individuals naturally, even when other people aren’t trying to induce their occurrence. It’s easy to rush when trying to get to work on time and then get frustrated with the slower drivers who seem to be parked in the passing lane. It’s impossible not to become so comfortable with the routine of our daily commute home that we eventually start to arrive in the driveway with no conscious recollection of how we got there. And although most people don’t have to contend with a hurry-up offence on a daily basis, we all end each day fatigued by our hurry-up lives.

These stressor states are built into our daily existence and reliably lead to unintentional errors that waste our time and money, damage our relationships, and occasionally get us or our loved ones seriously hurt or killed.

Neuroscience—Learning to Recognize SIF Potential at a Subconscious Level

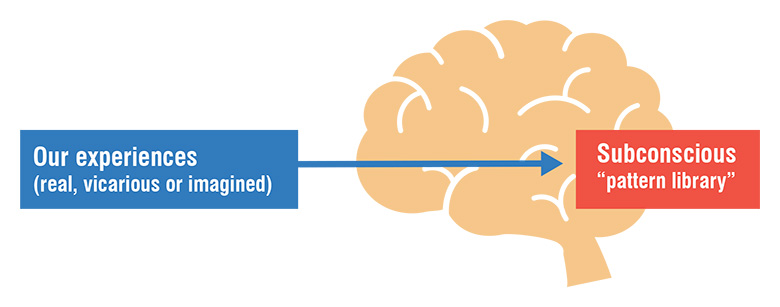

Human brains are designed to automatically learn to recognize and fear hazards and environments that have hurt us in the past. One of the built-in teaching mechanisms used to create this subconscious avoidance response is pain, or what many old-school grandparents refer to as the school of hard knocks. Pain is hardwired into each of us so that we can learn from our repeated injury events and begin to build a “pattern library” associated with injury and suffering in our brain. Eventually, these experiences cause us to begin responding automatically at a subconscious level to the environments and hazards associated with these painful events. This primitive part of our brain cannot communicate in language so we are made aware of the danger with an emotional or “gut” reaction like fear or uneasiness. This in-the-moment response eventually helps us to avoid interacting with the same hazards and environments when we encounter them again in the future.

The problem with using pain as the primary teaching tool in a SIF context is obvious—if enough hazardous energy is present then we may not survive enough lessons to develop an automatic response. Repeatedly falling off the top of a ten-story building is not a good way to develop a fear of heights. The good news is that the subconscious part of our brain that builds our individual pattern library can’t distinguish between real and virtual exposures. This inability explains why someone will react emotionally to a sad storyline in a movie and may need to reach for the tissues (even though they know at a conscious level that the story is fictional). It’s also the reason why so many people who have never interacted with sharks have nonetheless developed a fear of them by watching movies like Jaws or shows like Shark Week.

Because the subconscious functions of our brain can’t distinguish between real and imagined events, they can be rewired in at least three ways to add to our safety pattern library:

- Reframing past experiences—new lessons from the school of hard knocks

- Vicarious experiences—learning from the stories of others

- Imagined experiences—thinking about and picturing the possible severe negative outcomes after a minor injury or close call when serious injury potential exists

Using Three Types of Experiences and the 3Qs Technique to Avoid 24/7 SIF Risk

One way we can build our safety pattern library without risking further pain and suffering is by using a simple technique to analyze close calls and minor injuries. From an efficiency standpoint, this technique only needs to be employed when enough hazardous energy was present in the event—such as stepping off the curb and narrowly avoiding being run over by the bus—that a much more serious outcome was a reasonable expectation. In these circumstances, people need to make it a habit to always ask these three questions:

One way we can build our safety pattern library without risking further pain and suffering is by using a simple technique to analyze close calls and minor injuries. From an efficiency standpoint, this technique only needs to be employed when enough hazardous energy was present in the event—such as stepping off the curb and narrowly avoiding being run over by the bus—that a much more serious outcome was a reasonable expectation. In these circumstances, people need to make it a habit to always ask these three questions:

- What’s the worst thing that credibly could have happened given the circumstances? (To build the pattern library, you want to mentally paint the picture by imagining sights, sounds, smells, and physical consequences.)

- What human factor errors were involved in the event? (Why did you take your eyes off potentially lethal hazards and put yourself in the line of fire of the moving bus? Were you distracted by your cell phone?)

- What precursor states negatively influenced you at the time? (For example, walking in traffic and talking on the cell phone is a case of multitasking, which is a form of rushing.)

Experts in the neuroscience of learning estimate that a minimum of 40 repetitions are required to establish a habit. With sufficient repetition, people can begin to automatically add imagined experiences to their subconscious pattern library whenever they experience a SIF potential event in the future. The same 3Qs technique can be employed when others share their SIF potential events with us or when we virtually experience an event through media. These new virtual experiences, combined with their own set of real experiences, enable us to respond automatically to stressor states and the presence of hazardous energy that contribute to almost all 24/7 SIF events. Because this danger response occurs at a subconscious level, it meets the criteria of simplicity, portability and personal value required for 24/7 adoption.

Over the last 20 years, we have seen a human factors approach substantially reduce injury rates for millions of workers in organizations around the globe. But the biggest reason people should consider a 24/7 human factors approach to combat SIFs is that it’s the only approach that is effective in any context.

Remember, almost all SIF events occur outside the traditional workplace where the leverage of safety professionals is limited. If we’re going to make a difference, it’s time to take the same 24/7 approach to employee safety as we always have taken for employee health.

Click here to watch a live presentation based on this paper.

Don Wilson has more than 25 years’ experience in industrial education, safety and health training, and instructional design. He is a frequent speaker at corporate safety and health meetings, as well as NSC, ASSP and VPPPA conferences.

Get the PDF version

You can download a printable PDF of the article using the button below.