This article by Larry Wilson originally appeared in the December 2000 issue of Safety Online.com

A noted consultant offers some tips to improve the effectiveness of observations in your behavior-based safety program.

Observations are the cornerstone of a successful behavior-based safety process. Unless the observers can make good positive observations, the process will run about as well as a car with a bad motor.

This is not to say that a behavior-based process will work very well without a steering committee, management support, or employee buy-in, but good observations are the engine that drives the improvement. Or, as a safety advisor from a major oil company once told me, “Eighty percent of the value (of the whole process) is in doing the observations.” He also found that increased participation in terms of number of observations tended to correlate more consistently with injury reductions than did other metrics like percent safe, number of at-risks, etc.

This is not to say that a behavior-based process will work very well without a steering committee, management support, or employee buy-in, but good observations are the engine that drives the improvement. Or, as a safety advisor from a major oil company once told me, “Eighty percent of the value (of the whole process) is in doing the observations.” He also found that increased participation in terms of number of observations tended to correlate more consistently with injury reductions than did other metrics like percent safe, number of at-risks, etc.

Another interesting comment came from an operator who’s been making observations for years. He said, “You know, I think I get more out of doing an observation in terms of keeping safety in mind than I do when I’m being observed.”

Certainly, one of the main benefits of a successful behavior based safety process is that people tend to develop an increased sense of awareness for critical behaviors both on and off-the-job, not just while they’re being observed. To this end, making an observation probably would help you keep safety in mind a bit more than when you were just being observed. It would also explain, or help explain, why increased participation correlated so well with injury reductions.

However, increasing awareness is just one of the objectives you may have in mind when making an observation. Depending on what you see, you might also want to correct an at-risk behavior positively. Or, you might want to say thanks, without being condescending, for the safe work you observed. But a good observation will support at least one of the three main goals or expected benefits of the process, which are to:

- Change at-risk behavior to safe behavior.

- Keep safe behavior from changing to at-risk behavior.

- Increase awareness (eyes and mind on task) and help fight complacency.

Obviously then, in order for the process to be as successful as possible, the observers must have both the observation skills and the communication skills to achieve these objectives. And although you really can’t put words into people’s mouths or do the looking for them, you can at least teach them the steps and strategies that have worked well for others.

Changing at-risk behavior to safe behavior

First of all, you’ve got to be able to see if anything is unsafe, which could be either a critical behavior from your checklist or from your own knowledge of the job.

As you approach the person you want to observe, what initial actions do you see? Are they rushing, are they watching what they’re doing or where they’re going? Are they in the line-of-fire (hit by something or caught in something)? Is there anything that could cause them to lose their balance, traction or grip?

What about body mechanics: Do you see any lifting, pulling, pushing or reaching with excessive force? Remember to look for these things first. You’ll have more time to observe for other things such as repetitive motions and using unsafe equipment, so you can look for those types of things later.

As you reach the person you were planning to observe, ask permission to conduct the observation. After observing the task or job for a few minutes, ask the person if they can stop and talk for a minute or two. If you happened to see an at-risk behavior or something that you thought might be at-risk, it’s usually a good idea to ask them questions instead of telling them what they did wrong.

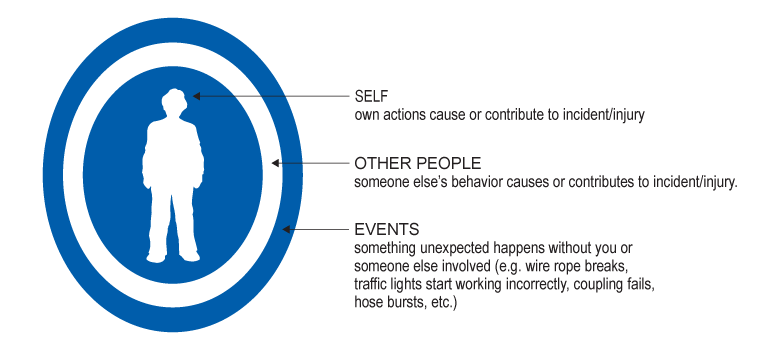

Since there’s usually a number of other factors that would also have to be present or lined up in order for an injury to occur, it’s a good idea to talk about all the factors, not just the at-risk behavior. Questioning them about the consequences if something unexpected happens can also be very effective. There are three sources of unexpected events: the equipment you’re using does something unexpectedly (for example, when driving, the brakes fail); the “other guy” does something unexpectedly (for example, a coworker starts up a forklift and begins to move forward without signaling people standing in front of it); or you do something unexpectedly (for example, lose your balance and fall).

Generally speaking, people are more receptive to the “other guy” making a mistake or the equipment doing something unexpectedly than they are to the possibility of making a mistake themselves, so you can use these areas without the potential for conflict.

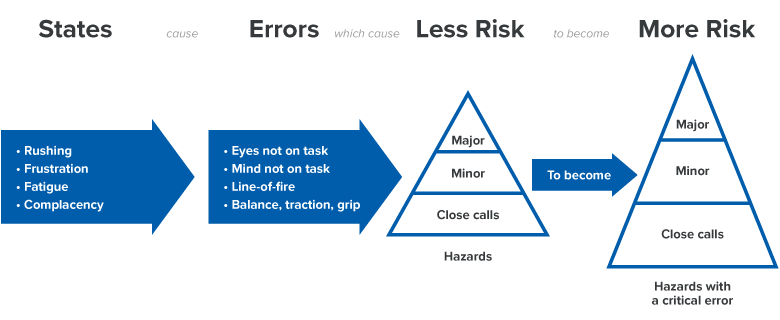

However, most injuries aren’t caused by equipment failure or the other guy. If you’re asking someone about the possibility of making a mistake that could get them hurt, don’t just say “sooner or later you’re going to make a mistake.” Instead, try making it a little more plausible by putting in a state or human factor. For example, “What if you were in a real rush, or you were really tired…?”

There are four states that contribute to a very high percentage of all (acute) injuries. They are rushing, frustration, fatigue, and complacency. The errors they cause that can get you hurt are eyes not on task, mind not on task, moving into or being in the line-of-fire, and somehow losing your balance, traction, or grip. Learning how to ask questions that tie a state to an error is much better than saying, “Sooner or later, you’re going to make a mistake.”

Positive reinforcement and improving awareness

Saying “thanks for working safely” can sometimes sound (as mentioned before) a little condescending or patronizing.

Especially if what you’re saying “thank you” for is covered by rules or procedures.

For instance, saying “thanks for locking this out” when the company has a “zero tolerance” policy for lockout might very well elicit a response like, “You’re welcome. Are you going to thank me for showing up for work today too!” One of the easiest ways to overcome this is to tackle positive reinforcement and improving awareness at the same time.

Instead of observing critical behaviors being performed safely and just saying thanks, try asking a few questions designed to get the person thinking. For instance, you could ask them, “If you could win $1,000 for predicting the next serious injury here—I don’t want to know who—but how do you think it would happen?” Or you could ask them, “What’s the most important thing to keep in mind—from a safety perspective—while doing this job?” Or you might even ask them some questions about off-the-job safety such as, “Between here and your house, what’s the most dangerous intersection or stretch of highway?” If they say the on-ramp to the freeway because of the construction, that just might be enough to keep them thinking on their way to work versus driving on “auto-pilot” when they get to that section of highway.

Instead of observing critical behaviors being performed safely and just saying thanks, try asking a few questions designed to get the person thinking. For instance, you could ask them, “If you could win $1,000 for predicting the next serious injury here—I don’t want to know who—but how do you think it would happen?” Or you could ask them, “What’s the most important thing to keep in mind—from a safety perspective—while doing this job?” Or you might even ask them some questions about off-the-job safety such as, “Between here and your house, what’s the most dangerous intersection or stretch of highway?” If they say the on-ramp to the freeway because of the construction, that just might be enough to keep them thinking on their way to work versus driving on “auto-pilot” when they get to that section of highway.

You could also ask them questions about knowledge and training; attitude, perspective and judgement; ergonomics and repetitive strain; and co-worker communication. Any questions that get the person thinking a bit more are good questions.

When you’ve discussed the job, the risks and potential for injury for about five to 10 minutes, you can say, “thanks for your time” as you’re wrapping up. It has the same effect as saying, “thanks for working safely,” but it doesn’t have the same condescending ring to it. In addition, you’ll probably get some good ideas from these discussions, in which case you can say, “Thanks for your input or suggestion” and again, provided it was a good suggestion, there’s nothing phony or condescending about your response.

Although everyone has a different style, as long as the observers can correct at-risk behavior positively, reinforce safe behaviors effectively, and increase awareness, then safety performance will improve (provided all other components remain intact). And, just like any other skill, making good observations takes time and practice. However, the return on investment, in terms of injury reductions, is well worth the effort.

Larry Wilson has been a behavior-based safety consultant for over 25 years. He has worked with over 2,500 companies in Canada, the United States, Mexico, South America, the Pacific Rim and Europe. He is also the author of SafeStart, an advanced safety awareness program currently being used by over 2,000,000 people in 50 countries worldwide.

Get the PDF version

You can download a printable PDF of the article using the button below.