By Danny W. Smith, SMS, CIT

Distractions have become a natural part of daily life for most people. Unfortunately, they’ve also become a cause of many daily fatalities.

And not just while driving—although that’s certainly what comes to mind when we think about the subject. But distractions are prevalent in most areas of our lives. So it’s not really a question of if we get distracted, it’s a question of when.

And not just while driving—although that’s certainly what comes to mind when we think about the subject. But distractions are prevalent in most areas of our lives. So it’s not really a question of if we get distracted, it’s a question of when.

A big part of the problem is the fact that our brains are simply not wired to be constantly on high alert. We don’t need to delve too deeply into neuroscience to know that everyone’s mind prioritizes what to focus on and then relegates certain routine tasks to our subconscious mind. This leaves our conscious mind to deal with the situation or the crisis at hand. That’s why we can do things like drive home from work without thinking. We’ve driven the route so many times that our subconscious mind takes over and guides us through the motions. If you’ve ever moved to a new house and then found yourself sitting in your old driveway a week later, waving to the folks who bought your former house, you know exactly what I’m talking about.

When I speak at conferences and with clients about distracted driving, I often talk about the different types of distractions. There’s a 2011 study, developed by the Governor’s Highway Safety Association, that separates distractions into four different categories. While this particular study focused on roadway incidents, the four categories of distractions it describes can apply to any task and they’re not limited to driving.

Four Types Of Distractions

The first type of distraction mentioned in the study is a visual one. It’s pretty self-explanatory and involves looking at something other than the task at hand, which can then lead to serious incidents. In SafeStart terminology, eyes not on task can increase the likelihood of an error with either line of fire or balance, traction, and grip. In a vehicle, a visual distraction could be any number of things. A person walking down the street, a billboard, an accident on the other side of the highway (although I’ve never understood why our side needs to stop when there’s nothing hindering the traffic), or simply looking for a specific street.

In industry, there are lots of visual distractions. Workers can glance at a forklift passing by their workstation, losing focus for just a moment. They could be reading a text message while walking back from the breakroom. Or they could just be looking at a coworker while having a conversation and working on something at the same time. Interestingly, this last example contains two types of distractions, leading us to the second type—auditory distractions.

The conversation between coworkers mentioned above would qualify as a potential auditory distraction. Personally, I know I’m affected by a lot of auditory distractions. I’m a musician. I play bass guitar and drums, and I sing a little (although most people who have heard me sing are usually glad that I sing only a little). While I prefer some musical styles over others, I do listen to a lot of different stuff. Very often, I listen for specific parts to play or sing. But this can be a distraction. Focusing on what I’m hearing instead of what I’m doing can be risky, especially if what I’m doing requires my undivided attention.

And it’s not just limited to music for me. I listen to talk radio a lot as well and I’ve got a bit of a bad habit when I do this: I argue with the talking heads from the radio shows. I don’t mean I call in and argue. No. I do it in the privacy of my truck! Often when my wife is with me, she will reach over, gently pat me on the leg and remind me, “Honey, they can’t hear you.” “No, but it makes me feel better!” is usually my pointed response. I bet I’m not the only one who does this and although these are my personal examples, they show how a simple auditory distraction can affect us.

The third type of distraction is a manual one. In a vehicle, this might be adjusting the seat, changing the radio station, moving a mirror, or even reaching for a toy a baby dropped in the backseat. At work, we could temporarily lose focus and stop giving all our attention to a machine’s operation by simply turning a control knob. Or we could be performing a repetitive manual task with something unexpected coming in contact with our hands. Repetitive manual tasks could also be the cause of our mind wandering or becoming preoccupied, which brings us to the last type of distraction.

The fourth type—a cognitive one—is in my opinion, the most dangerous kind. This goes back to how our brains “sort” different activities into the conscious and the unconscious mind. Things that we’re familiar with or do on a regular basis are exactly the things our mind conveniently relegates to the subconscious mind. These are the situations we tend to make comments about such as: “I’ve replaced this gear so many times I could do this in my sleep” or “I’ve driven this stretch of the road so often I could do it with my eyes closed.” This is also when you can accidentally hit REPLY ALL instead of REPLY on an email (that can get you into a world of trouble).

I find this is especially true when you have a lot of other preoccupying things going on. Let’s say you have a sick child at home, you’re reflecting on a call with your boss that didn’t go well, you’re thinking about a presentation you have to do tomorrow, or you’re considering how to best fix a quality problem—all of these things can become the primary focus in your conscious mind, becoming cognitive distractions.

At-Risk Behaviors

Take the at-risk behavior of using a cell phone while walking or operating heavy machinery— be it for an actual call, a text, or using an app. Many would consider this to be deliberate at-risk behavior and I’m not going to argue that point. However, it’s my opinion, and I know lots of people agree, that we’ve also reached a point in our society where this is not only deliberate but also simply habitual and people do it without thinking. In fact, it’s so common that a lot of companies that I talk to have had to ban cell phones on their shop floor because they’re such a distraction.

Take the at-risk behavior of using a cell phone while walking or operating heavy machinery— be it for an actual call, a text, or using an app. Many would consider this to be deliberate at-risk behavior and I’m not going to argue that point. However, it’s my opinion, and I know lots of people agree, that we’ve also reached a point in our society where this is not only deliberate but also simply habitual and people do it without thinking. In fact, it’s so common that a lot of companies that I talk to have had to ban cell phones on their shop floor because they’re such a distraction.

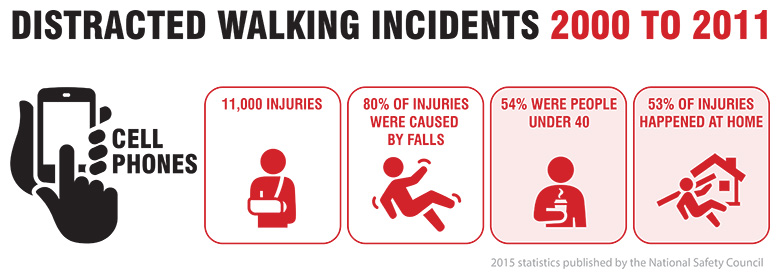

In 2015, the National Safety Council began publishing statistics related to cell phones and distracted walking. Did you catch that? Not distracted driving, distracted walking! They found that between 2000 and 2011, walking incidents with cell phones accounted for more than 11,000 injuries, with nearly 80 percent of those resulting from falls. And 54 percent of them affected folks under the age of 40, so this is a bit more than the old “Help, I’ve fallen and I can’t get up.” These incidents were not happening in unfamiliar places either—53 percent of them happened at home. It’s clear that distractions happen everywhere—at home, at work, and on the road—so we don’t just have a distracted driving problem, we have a distracted lifestyle problem.

There are many additional studies and statistics, but let me quickly mention one more. The 2013 Safe Kids Worldwide study looked specifically at distractions with students because they determined that 50 percent of pedestrian deaths at the time were teenagers between the ages of 15 and 19. In their study, they observed teenage students as they were crossing streets near their schools and found that 20 percent of them were distracted by cell phones, headphones, or other electronic devices. And just think about it: it’s just a single snapshot in time. I’m sure that the others, who were not viewed as being distracted at that exact moment, probably faced the same issue at other times.

It’s also important to note this study took place in 2013. Where are those students now? If you’re thinking they’ve probably graduated and are now on our shop floors or in our offices, you’re right on target. So do you suppose they’ve gotten better in dealing with distractions over the past few years? I’m going to go out on a limb here and guess that they probably haven’t.

Building Habits

We usually don’t get better at something accidentally. It takes planned and intentional activities to build new habits. We’ve all heard the phrase “Practice makes perfect”, but I think it’s simply not true. I’ve found you can practice doing something the wrong way and get really great at screwing it up every time. If you ever saw my golf swing, you would understand that perfectly! What practice really makes is permanence.

At SafeStart, we talk a lot about working on and practicing good safety-related habits. I’ve found this is a great skill set to utilize when it comes to distractions. But there’s a lot of confusing or inaccurate information out there regarding habit formation, and I’m sure you’ve probably heard some of it yourself. Things like “if you do something 21 days in a row it will become a habit”. Well, that’s simply not accurate. According to the researchers from University College London, there is no magic number and building habits is different for everyone. A new habit can become automatic after an average of 66 days, but this number is only that—an average, which will only be true for some people but not for others.

Neuroscientists would tell us that when we’re practicing a new habit, we’re building what they call “preferred neural pathways”. What this means in layman’s terms is that we’re developing habit strength in our subconscious minds so that we can do things automatically without thinking about them. Those habits actually compensate for complacency—including the times when we’re distracted.

An example I like to use is holding the handrail while walking up or down the stairs. It isn’t a natural thing for us to do and we have to learn to do this consistently. When we first learn this habit, we approach a set of stairs and have to think “reach for the handrail”. But over time, we get to the point where when we start to go up the steps, our hand automatically reaches out without us having to think about it—that’s when true habit strength has been developed.

If you’re older, like me, you can probably recall a time before seat belts were required to be worn in vehicles. Heck, my first car didn’t even have seat belts! Granted, the car was much older than I am, but those of us who had been driving for a while when these laws came in force had to learn the new habit of putting on the seat belt. Fast forward a few decades and now it feels a bit weird if you get into a vehicle and don’t put your seat belt on immediately. In fact, when most of us get in a car or truck, the first thing that happens is our arm reaches over our shoulder for the seat belt without us consciously thinking about it. This is true habit strength.

If we want to overcome distractions, regardless of their source and location, one of the best techniques I’ve found is practicing those good safety-related habits and getting them to solid habit strength. Because, as I said in the beginning, it’s not a question of if we get distracted, it’s a question of when.

Over 25 years of EHS management experience in several industries provide Danny with a foundational knowledge that is applicable to all environments. He was among the first safety professionals to ever receive the BCSP Safety Management Specialist (SMS) designation. Danny is committed to continuous learning, remaining informed about the current developments in the EHS industry, and regularly expanding his area of expertise. He garners accolades from both conference organizers and his session attendees whenever he delivers a presentation thanks to his ability to connect with any audience and to put them at ease.

Get the PDF version

You can download a printable PDF of the article using the button below.