This article by Larry Wilson is reprinted with permission from the

January/February 2001 Issue of OHS Canada Magazine

Driving to work, we call it “defensive driving”. It’s basically, “never mind who or what’s at fault, I’m here to protect myself from getting hurt.” That same philosophy can apply at work.

Why is it that some people can accept how important the behavioral and attitudinal component is on the highway, but have so much trouble bringing these concepts into the workplace? Maybe it’s because the stakes are higher (four times more fatalities). You know from your own driving experience that you have to look out for the “other guy” when you drive a car. If you drive a motorcycle, you have to learn to drive so defensively that they teach you to “drive as if you’re invisible”.

Getting people to accept this responsibility isn’t difficult. It isn’t a matter of right or wrong, or who’s to blame. It’s a matter of survival. Just because you have the right of way doesn’t mean you should pull out in front of a transport truck. We all know the truck has “right of weight”. None of us wants to be dead right—so we look out for the other guy.

We don’t know or care about the other guy. We may never see him or her again. We will not be saying hello, doing lunch, playing softball or anything of the sort with the other guy. Our interest is purely selfish—we don’t want to get hurt, or killed. Heck, we don’t even want to be inconvenienced by a fender bender. So, we try to anticipate errors, like turning without looking, or turning without signaling. We also look for other behaviors like tailgating and weaving in and out of traffic, and we use these observations to predict what that driver will do next (eg. won’t likely stop at a yellow light). I know, I know, some people don’t use this in the safest manner. Since they know the guy is going to run the yellow, they accelerate too, so they can get through with him…

But the point is, we don’t have any trouble with observation, behavior and error when we’re driving. We may not like what we’re seeing but we don’t ignore it, nor do we pretend these concepts aren’t important.

When it comes to error, at least from a “prevention” point of view, not from a “when the lawyers get involved” point of view, ownership and responsibility aren’t an issue either. I don’t know about you, but I would much rather trust me to look out for the other guy—than have to trust the other guy to be looking out for me… Now thankfully, the other guy was looking out for me—here and there—when I did make a mistake like eyes not on task (didn’t see the car) and he swerved to avoid the collision. But very few people would say, “It’s his responsibility to look out for me even if I make a mistake”. Even fewer would say it’s the police’s responsibility to protect me from driver error, especially my own.

Although we might think it’s partly their responsibility to protect us from drunk drivers, excessive speeders, etc., we know the police are only going to affect deliberate at-risk behaviors. Someone who doesn’t see a stop sign or red light (honestly—not someone going through a very yellow light), didn’t mean to go through it. They just didn’t see it! And, by the way, “they” isn’t really “they” or “them”, it’s us. Almost everyone has gone through a red light or stop sign without even seeing it, or seeing it too late to do anything about it. But since we’ve all “been there” so to speak, we know that you should still look both ways before entering the intersection—because, as mentioned before—the cement mixer has “right of weight”.

When we hear statistics like 95% of all traffic wrecks and fender benders are caused by driver error and only 5% by weather conditions, road conditions or the condition of the car—most people don’t have any trouble with it.

But, considering that most of us are equally motivated not to get hurt or killed anytime or anywhere, is it likely or unlikely that error plays the same major role—anytime, anywhere? Or is it different on the highway than it is at home or at work? Are you ever trying to make any mistakes? Can you pick where and when you’re going to make a mistake? (I’ll pick eyes not on task next Thursday at an intersection…)

Certainly, it’s easier to minimize or even eliminate the negative consequences at work if someone does make a mistake. If you guard a sprocket and someone hits the guard with their hand, virtually nothing (bad) happens. Whereas, if you hit a guardrail on the highway, it could be a lot worse. But how many “unguarded sprockets” (figuratively speaking) have you been injured by?

When you look at the anatomy of an acute injury, we all know that there are usually a number of contributing factors. In order for an incident or injury to occur, the factors have to be lined up “just right” and then something unplanned or unexpected has to happen.

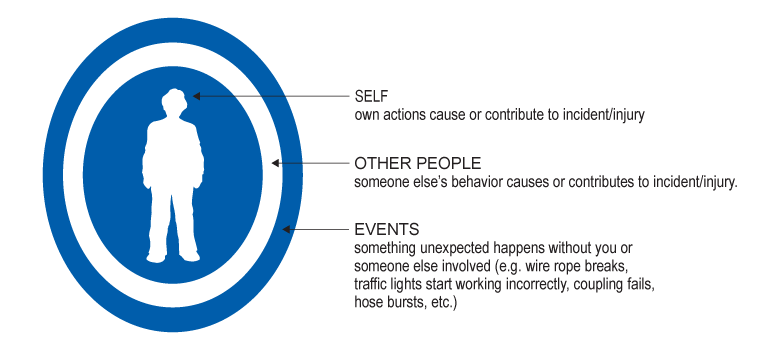

Figure #1

There are only three sources of unexpected or unplanned events. Either you do something unexpectedly, someone else does something unexpectedly or the equipment does something unexpectedly (see Figure 1).

Since you don’t really know about anyone else (because you never know exactly what they were thinking or not thinking about at the moment they got injured), just think about your own injuries and serious close calls for a minute. How many were caused by equipment failure? How many were caused by the other guy (not including contact sports)? Now ask yourself what’s left. Remember to include all the cuts, bruises and scrapes you’ve had in your analysis. What percentage of your own injuries were in the “self area”? (For most people, it’s well over 90%.) Granted, not all of them could have killed you, but some could, and even if you only banged your shin, were you trying to hurt yourself? Not likely! So, for the injuries you’ve had in the “self area”, when it wasn’t the equipment or the other guy—what was the unexpected occurrence that set off the chain of events?

If you weren’t trying to hurt yourself, then you must have done something unexpectedly to hurt yourself. Unless it was a spastic nerve twitch, you must have made a mistake, an error or a miscalculation of some kind. And, more to the point, why then? I mean, it’s not like you’re always making mistakes. You don’t slam a finger in a car door every time one closes around you. You don’t bang your shin every day, just like you don’t slip and fall walking very often. And since we’re never trying to make any mistakes, let alone any injury causing mistakes, to go after the problem reactively by blaming the person for making a mistake like not seeing the oil spill or not seeing the ice—is useless, or worse. However, to go after the problem pro-actively by training people to make fewer injury causing mistakes isn’t useless at all. It works on the highway in terms of defensive driving concepts—and works everywhere else too.

What are injury causing mistakes? Well, in order to experience an acute injury such as a cut, bruise, broken bone or electrical shock, you have to come into contact with some hazardous energy or some hazardous energy has to hit or contact you. If it hits you, you could think of yourself as being in the path of the hazardous energy or line-of-fire, and in order for you to move into it, well, you’re not going to move into it if you see it or you’re thinking about it, unless somehow you slip, fall or skid and move into it inadvertently. Or, to put it differently:

- either you didn’t see the hazard (eyes not on task);

- you weren’t thinking about the hazard (mind not on task);

- you were in, or moved into the line-of-fire;

- or somehow you lost your balance, traction or grip.

Although getting it down to four errors seems efficient, you can’t ask people to filter out a subset of mistakes, because you’re not trying to make any mistakes ever. It’s like telling someone, “Don’t forget your wallet, don’t forget her name and. . . oh yeah, don’t get hit by a Mack truck on your way to the restaurant.”

But if you go back to the “why then?” in terms of why did you make a mistake at that moment, there is a significant pattern that emerges. Think about some of the injuries you’ve had, or close calls that were in the “self area”. At the time, (or at the moment) were you thinking about what you were doing, or the risk of injury, or were you thinking about something else? (Most people weren’t looking at their hand or thinking about cutting themselves when the knife contacted them.)

Why weren’t you thinking of the risk? When you let your mind wander from the risk, it’s usually because you’ve become complacent with the hazard. How do you fight complacency? The standard or “pat” answer is that you must “increase awareness” either by reminding people of the risk or reminding them to focus on the job, pay more attention, etc. However, complacency isn’t a deliberate process. You’re not trying to become complacent or more complacent. It’s a natural process that creeps up on you, like aging.

And, although it’s not as guaranteed as aging, complacency can kill you, especially when you’re driving. So people take defensive driving courses to minimize their chances of being hurt or killed by the “other guy”. Who, among other things, might very well be complacent and turn without looking…

But, since there are more single vehicle fatalities than multiple vehicle fatalities, defensive driving does more than just helping to protect us from the other guy. It also helps to keep us focused, which reduces the chances that we’ll make a mistake. Observing other people almost automatically makes us evaluate our own behavior. So once again, we’re thinking about what we’re doing vs. driving on “auto-pilot”. (The trouble with “auto-pilot” is that you’ll be a split second slower to react compared to your reaction time if you were focused.) Observing others is probably the best way to stay focused and fight complacency leading to mind not on task (which can lead to other injury causing errors).

How much is complacency a factor in workplace injuries? Well, over 25% of all injuries happen to people with ten or more years of experience on the job… but who really knows? (Hardly anyone is going to tell you that they weren’t thinking about what they were doing when they got hurt.) So once again, it’s probably better to just ask yourself how often has it been a factor in the injuries and close calls you’ve had? If you’re like most people, it’s been a factor—even if it’s not been the main one—in almost every case. Observing others is probably your best bet for fighting complacency.

However, defensive driving techniques involve more than just observing other drivers to anticipate what they’ll do next. You will also be encouraged or coached to improve your habits. Because even if you’re doing a better job of observing others what about when you’re driving through Saskatchewan? (Wake up, you’re missing it, it’s another wheatfield, get your camera!) And, it’s not like you can rely on the scenery to keep you focused. However, this would be equally true for the view from the 401 in Toronto, and equally true for a routine job someone can do in their sleep (or on auto-pilot).

So you learn in defensive driving that you must work on your habits, to compensate for those times when your mind does go off task, e.g. you learn to follow at a safer distance using a three second rule instead of the two second rule. They teach you to practice doing shoulder checks when changing lanes, even if you are in Saskatchewan—that way you’ll “always” do it on the 401…

Ok, so you’re observing others more often and more closely to help fight complacency leading to mind not on task and you’re working on your habits in case your mind does go off task (and it will on long drives or routine jobs), but is that it?

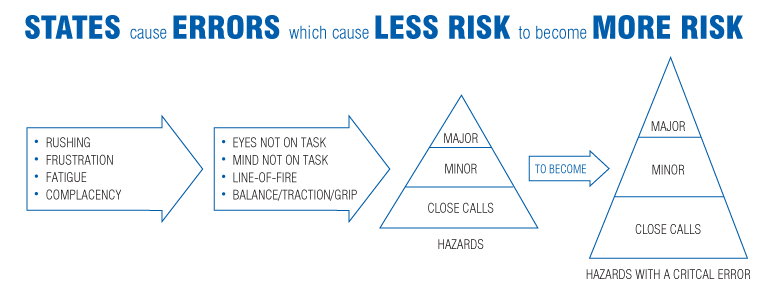

Well, it may be in terms of what you got from your defensive driving course. But there is more. Habits are only good if you’re doing the task the way you normally do it, or at the pace you normally do it, etc. If you add enough rushing, frustration or fatigue to the equation you can easily push anybody past their habit strength.

Over 25% of all injuries happen to people with ten or more years of experience on the job.

For instance, you’re probably pretty comfortable going 100–120 km/hr on a major highway if conditions are good. Suppose we put you into an Indy 500 car and you now had to go over 200 mph on the straightaways just to keep up. What are the chances that you might be just a little too touchy with the steering wheel or the brake when you came to the first corner…

In other words, we don’t have “habit strength” at 200 mph because we don’t go 200 mph. We don’t even go 200 km/hr (except in Toronto). So you can’t rely on habit strength alone, because if you’re really rushing, your habits might not be enough to keep you from making an error like eyes not on task or losing your balance, traction or grip. And while there are many states or human factors that cause errors—rushing, frustration, fatigue and complacency cause a very high percentage of the injury causing errors.

How high a percentage? Well, once again, just think of your own injuries. Can you think of a time you’ve been hurt (in the “self area”) when you weren’t rushing, you weren’t frustrated and you weren’t tired? If so, were you complacent? Now you can’t “notice” complacency so you have to observe others and work on your habits for that one. But you can notice rushing, frustration and fatigue. The last technique you’d need, would be to analyze any small errors or close calls and ask yourself if it was a habit that still needs work, or if it was a state that you didn’t notice or recognize quickly enough to prevent making the error. This will give you the ability to improve over time.

But, despite the efficiency of improving behavior and reducing error, many companies are reluctant to approach the issue because they do still have a few “unguarded sprockets” here and there. If this is the case, then fix them so you can move on. Fix more than might be efficient or cost-effective so your workforce doesn’t think you’re just dumping it all on them. But get at the people side of it or the human being side of it, as quickly as you can. Because, like it or not, us human beings make mistakes. Some of those mistakes get us hurt and you can’t engineer all of the jobs and all of the tasks to such a degree that all injuries will be avoided.

It is just like it is on the highway, except that it’s easier to eliminate the possibility of an injury if people do make mistakes in the workplace. Unfortunately, because we can do more in the workplace, there’s a natural tendency for the people themselves to do less, or to shoulder less responsibility for their own actions or mistakes. It’s easier to say, “The cord tripped me” than it is to say that “I tripped on the cord because I was in a rush and I didn’t see it.”

But we all know the unsafe condition wasn’t the sole contributor. We know we have to play “heads-up ball” on the highway because you can’t, I can’t and they can’t eliminate all the hazards or hazardous energy out there. And if you go to workplaces that can’t be re-engineered or controlled, you get the same type of mentality or sense of responsibility that you do on the highway.

Some of the best skills, in terms of playing “heads-up ball” that I’ve ever observed were with loggers on Vancouver Island. They know there are moss covered sink holes in the summer, snow covered sink holes in the winter and dead wood that can give way any time of year. Maintaining your focus and vigilance is critical. Another group of workers who have a good sense of responsibility are Ironworkers. Ironworkers talk a lot about focus, in much the same way athletes talk about being in “the zone”. I had one Ironworker ask, “Why do you call them hazards?” I said, “Well, without a source of danger, you can’t get hurt”. I asked, “What do you call them?” He said, “We just call them mistakes.” How simple—yet how smart. Because for them, the hazard is ever-present.

If the stakes are high enough, people take on a lot more responsibility for error. Both in terms of preventing their own and anticipating it in others. However, whether it’s because the stakes aren’t as high or whether it’s for another reason, people don’t in general bring their defensive driving package into work.

But, if you want significant reductions in injuries (60–90%), you won’t get it by guarding the back of the machine or doing WHMIS refresher training. The only way you’ll get those types of reductions is if you can get your employees to bring their defensive driving skills into the workplace. You may have to provide this type of training because not everyone has had it. But you’ve got to get them to realize that it really isn’t any different than it is on the highway—it’s just that the stakes aren’t as high.

Now, all that needs to be done is to bring these concepts and techniques into the workplace. However, if you do have unguarded sprockets, then bringing defensive driving and error reduction techniques into your workplace may not be very “efficient” from an injury reduction point of view. On the other hand, it isn’t likely going to be very efficient to wait until everything is perfect either. There are so many injuries like slips and falls that are not going to disappear until people improve their habits with eyes on task and balance, traction or grip.

Larry Wilson has been a behavior based safety consultant for over 25 years. He has worked with over 2,500 companies in Canada, the United States, Mexico, South America, the Pacific Rim and Europe. He is also the author of SafeStart, an advanced safety awareness program currently being used by over 2,000,000 people in 50 countries worldwide.

Get the PDF version

You can download a printable PDF of the article using the button below.