Complacency can happen to anyone, anywhere. It’s not just something that happens at work, it can also occur at home or while driving. When a person becomes comfortable with what they’re doing and no longer thinks about any associated hazards, that’s complacency. It’s dangerous and difficult to recognize, but there is a natural reason our minds and bodies go on autopilot.

The word complacency is congruous with its definition in that it doesn’t strike fear in anyone. When people are in a state of complacency, they aren’t thinking about the risks waiting to harm them around the corner. The word isn’t threatening in the same way people don’t feel threatened when they’re in that state of mind.

Because of that, complacency is one of the most underrated causes of human impairment. Even though it is widely recognized as a problem, complacency is often underacknowledged as a contributing factor when more prominent causes like fatigue or rule-breaking are available to cite more easily. But when companies fail to mitigate complacency’s potential effects, does that mean that complacency is a choice?

Complacency is a natural human function, mostly subconscious and usually only identified in oneself retrospectively. With that information alone, it would be easy to say that no, complacency is not a choice.

But if you’re reading this, there’s a good chance that you’ve identified complacency as a problem, so you must realize there is some level of choice, especially when seeking to prevent workplace incidents and injuries.

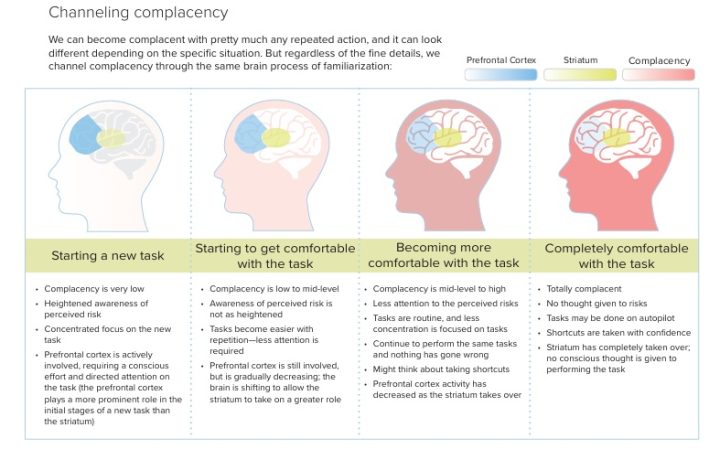

One journal paper shows that complacency is a neurological function of the brain. The prefrontal cortex (the front part of the brain responsible for seeing and predicting the consequences of behavior, decision-making, reasoning, problem-solving, and regulating emotions) and the striatum (which is interconnected with the prefrontal cortex and functions as the intermediary between emotions and actions) work together, and every time you do something new, they fire on all cylinders to process the new task. However, as the task is repeated, the action gets easier and fewer neurons fire. The brain no longer requires the prefrontal cortex and the striatum to take over to complete the task as a habit.

We can become complacent with pretty much any repeated action, and it can look different depending on the specific situation. But regardless of the fine details, we channel complacency through the same brain process of familiarization:

Channeling complacency

This example will walk you through the channeling complacency model. Since complacency can happen in any industry, it’s helpful to look at a detailed real-world example that most of us have gone through—driving—to help recognize the pattern in action.

Starting a new task — Learning to drive a car/forklift

Think about when you first started learning how to drive a car. Driving is one of the riskiest things we do, yet most drivers become so comfortable with the task that they no longer think about the risks involved. New drivers, however, are very aware of the risks and are most likely to do everything by the book in order to stay safe. Tasks in this stage are performed at full attention, and complacency is very low. This checklist resembles all of the things that drivers should do when they are about to set out on the road to stay safe (it is not a comprehensive list and should only be referenced for this example). At this stage, the prefrontal cortex and the striatum have the checklist at the ready and adhere to it more strictly to prevent the risks from turning into costly errors or injuries.

□ Do a circle check around the vehicle to identify any safety issues on or around the vehicle before starting a drive.

□ Inside the car, adjust the mirrors and seat and ensure all controls are set before putting the car into gear.

□ Putting on your seatbelt is another important step that happens before moving the vehicle.

□ Keep the radio off or the volume low to ensure it doesn’t interrupt concentration.

□ Place both hands on the steering wheel in the clock positions of 9 and 3.

□ Be cognizant of all of the rules of the road, scan for and identify all hazards.

□ Check mirrors often to be alert of your surroundings.

□ Brake and accelerate smoothly (count to three to ensure a full stop at a stop sign).

□ Maintain appropriate speed and keep a safe following distance.

□ Slow down before turns and signal intentions early.

□ Check blind spots with a shoulder check after signaling intentions before changing lanes.

□ Scan the road continually, especially approaching intersections.

This list can go on and on, but it’s a good example of how a new driver puts their entire focus on the new task checklist in the first stage of the channeling complacency model, having a heightened awareness of safety and a hyper-concentration on all of the risks surrounding the act of driving.

The same rules apply to learning to drive a forklift in the workplace.

□ Do a visual circle check before starting the forklift.

□ Do an operational check to make sure the forklift and controls function appropriately

(similar to what is performed inside a car).

□ Putting on your seatbelt is a must in forklifts, too.

□ Use both hands to maintain control of the steering wheel.

□ Be cognizant of all of the rules of the floor, scan for and identify all hazards.

□ Adjust and check mirrors (if your forklift model includes mirrors).

□ Avoid sudden stops and drive at speeds appropriate for the job.

□ Maintain visibility—be aware of the forklift’s blind spots and take extra caution when backing up or turning.

□ Use a spotter when backing up or navigating tight spaces when visibility might be limited.

□ Use a backup alarm or horn when backing up to alert workers of the forklift’s movement.

□ Sound the horn at crosswalks and other areas with pedestrian traffic, slow down, and yield the right-of-way.

There may be a few rules that differ from driving a car, like sounding the horn when reversing/approaching areas with low visibility. And because of that, the first few times someone operates a forklift, they will likely keep that heightened awareness of safety, sticking to the checklist—even if transferable complacency creeps in for familiar tasks from the experience of driving a car.

Another thing that can happen in the brain is transferable complacency. When a task is similar to one that has been performed before, your brain will more rapidly become familiar with it, requiring fewer neurons to fire to complete the task. While this can make the task seem easier to perform, the transferable complacency may also bring a lack of concern for associated risks due to the supposed familiarity of the task. Those blind spots can lead to negative consequences unless you do something to mitigate your complacent state of mind.

This blog post is an excerpt adapted from Fighting Familiarity: Overcoming Complacency in the Workplace. It defines complacency, discusses individual and organizational complacency, offers insights into its contributing factors, and provides a straightforward overview of what organizations can do about it. Download it to proactively reduce complacency in your workplace.