By Gary A. Higbee

Want to change your company’s safety culture? Forget about culture and focus on the change.

Every company has a culture at the corporate level. In most corporate handbooks that culture is intended to produce similar cultures at each facility managed by the corporation. But we all know that’s not always the case. In practice, every site has a different culture. This can present a number of challenges for corporate-level safety managers to implement an effective safety system evenly throughout an organization.

Take a look at almost any organization that manages multiple facilities and you’ll see different levels of safety performance at each site. The culprit? Culture. In some cases a proactive safety culture leads to low injury rates and in others the SIF rate is frustratingly high year after year.

There are so many factors that go into producing a culture—age, gender, education, geography, local influences, and the interplay of a thousand tiny factors—that it is nearly impossible to tell what blend of causes are responsible for elements of a company’s culture. Culture can form at a glacier-like pace and feel just as difficult to move as a mountain of ice. It’s impossible to change culture overnight. To complicate things further, in the safety world you’re not just dealing with one cultural change. Every individual employee has their own unique safety culture, each facility in an organization has their own unique safety culture and the corporate office has its own culture. These cultures are often in conflict.

Despite these challenges safety leaders have one effective option to change a culture: forget about trying to enact a cultural change and focus instead on developing a workplace climate that takes safety seriously.

There are significant differences between an organization’s culture and their climate. The climate of an organization can be changed almost overnight. New safety systems, procedures, leadership changes can alter the work climate rapidly and effectively. Culture on the other hand evolves over time, often a long time. Those who wish to change an organization’s culture would be wise to first change the climate and then over time the culture will develop.

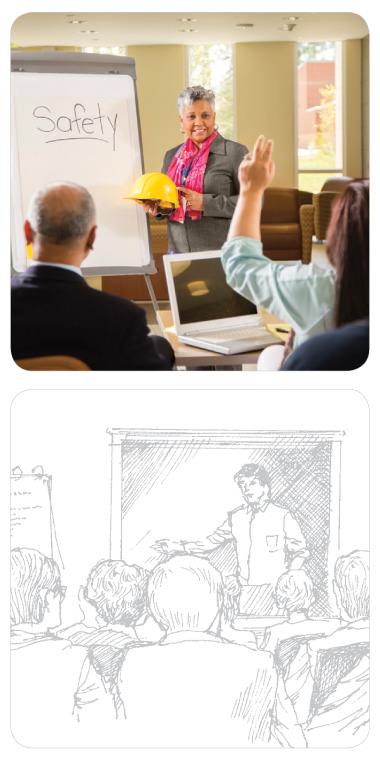

I’ve spent years studying safety and organizational change. When I speak about cultural change or lead workshops designed to develop a robust, effective safety culture much of our time is spent on what is required to manage difficult organizational change initiatives. It’s a pressing topic for many safety leaders and there are few ready answers.

However, one of the things I’ve noticed is that successful safety initiatives all follow the template for organizational change. Too often safety managers believe that their field operates under different rules than HR, operations and other corporate departments. This couldn’t be further from the truth. The safety profession has its unique challenges but it still follows the same guidelines that govern the corporate organization. By approaching safety change strategically it is possible to create a climate that is conducive to improving a safety culture.

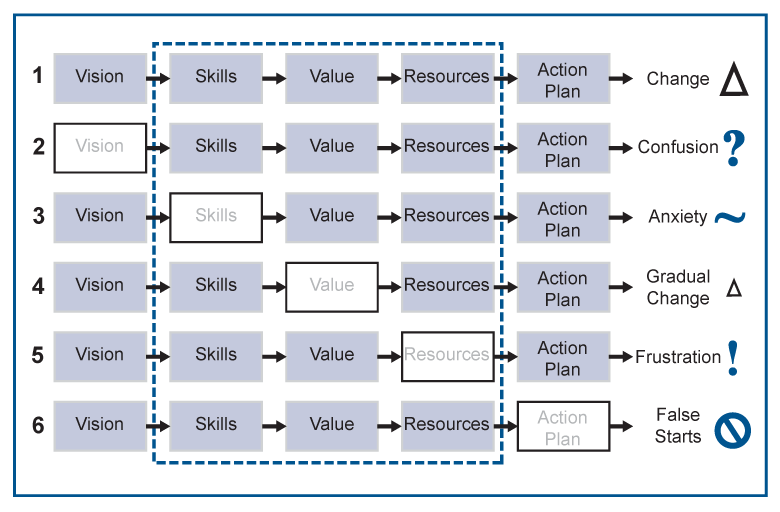

There are five essential components to any type of successful organizational change.

Vision

Everyone in an organization needs to be aware of what is being changed and why. They need to know exactly where the organization is and, where it needs to go. Vision often comes from upper management, although I’ve seen cases of a vision originating from other levels of an organization too. When it comes to safety, the vision proposition should clearly articulate the ultimate goal of the organization’s safety efforts and how safety fits within the larger organizational structure. Are you striving for zero injuries? Do you want to make employees safer at home as well as on the job? Your vision should clearly set out the main priorities you plan to work towards.

Action Plan

Once a vision is established a plan of implementation is required. This plan has to be specific to the vision and must outline the practical steps that will be taken to achieve the vision. As such, it should answer the question, “What do we need to do to meet the vision statement?” The plan must include input from all affected parts of the organization. Because safety is a concern for every department within an organization, any safety-focused action plan should cover every employee in the company. Once established, this action plan will be a road map to success, and sticking to it will help to avoid false starts and ensure everyone is pulling in the same direction.

Skills

The people who will execute the action plan must have the skills required to carry out the necessary tasks. For safety, this means that safety managers should have full working knowledge of compliance requirements and how human factors affect an organization’s overall safety performance. Workers should also be trained in both compliance and human factors. If the required skills aren’t present in the current workforce then employees will need to be trained or new employees hired to fill the gap. In many cases I’ve seen strong safety improvement plans fail due to a lack of skills.

Resources

Safety improvement requires management to dedicate sufficient resources—from financial support to necessary equipment and training time. Asking someone to perform a task without providing the required resources will likely set them up for frustration and anger, and could have lasting negative repercussions on an organization’s morale.

Value

Perhaps the most important element in changing a safety culture is creating a positive value system. Employees often view safety managers as naggers who constantly look over their shoulder and tell them what to do. Consequently, this can lead to a negative view of a company’s safety program. However, if you can help workers understand your safety efforts empower them by giving them the skills and resources they need to stay safe, rather than controlling what they’re allowed to do, then they’ll begin to see greater value in safety and be more receptive to change.

Putting the Components in Place

Changing a corporate climate requires executives to concentrate their efforts on the factors they’re able to effectively influence. Fortunately, even a single determined executive can positively affect each of these fives items noted above. A vision and action plan are best crafted at the executive level, in consultation with key stakeholders throughout the organization. Budgeting is also part of management’s responsibilities, and organizational leadership always has the option to commit the time and financial resources for skills and safety awareness training.

Value is the most difficult to influence because every employee has a different value system. However, most people have similar personal safety agendas. They want to stay safe so they can coach their child’s softball game after work, do work around the house on the weekend, and stay healthy so they can provide for their family. This is why off-the-job or 24/7 safety programs are so important, and appealing to these common threads will foster a collective belief in the value of your safety program. For many organizations personal safety skills training is a critical component of demonstrating value and encouraging positive long-term change in organizational culture.

The five components vary in scope but they are all equally important. Without including all five in any change initiative you will have a hard time creating the climate you want, and long-term cultural change will be nearly impossible. It doesn’t matter how noble your vision is if you don’t have an action plan to carry it out. Trying to develop skills without resources is a fruitless exercise. And employees will remain skeptical of your efforts if you can’t demonstrate real value. But get all five components in place and you’ll be setting your organization on a path to safety success.

Common Roadblocks to Changes in Safety

As I’ve just outlined, organizational change requires vision, perceived value, skills, resources and an action plan to achieve its stated goals—but while the presence of these factors is necessary for change, they aren’t enough to guarantee success on their own.

As I’ve just outlined, organizational change requires vision, perceived value, skills, resources and an action plan to achieve its stated goals—but while the presence of these factors is necessary for change, they aren’t enough to guarantee success on their own.

A general apprehension develops every time a change initiative fails, creating a natural resistance to change for a large part of the population. No one wants to waste their time or be inconvenienced when they think something is bound for failure. This is one of the reasons many workers roll their eyes or yawn whenever a new safety program is announced—they’ve seen this act before and they know it usually fizzles out with little meaningful change.

There are four common roadblocks that often hold up safety initiatives that are otherwise poised for success.

Overemphasis on Compliance

The first hurdle is getting past the notion that regulation is the prime component of improved safety performance. Most safety initiatives are focused on satisfying a regulatory requirement issue. It may be our initial starting point but it should not be our only approach; taking a compliance-centric approach will reduce regulatory liability but as we become more compliant injury rates are less likely to improve.

Better regulatory performance and injury reduction are two separate goals and confusing the two is to treat the means as an end. It’s a case of not seeing the forest for the trees. Any safety measure, from a tactile object like a handrail to a process like lockout/tagout, is only useful if it’s actually used. It’s possible for a facility to meet OSHA requirements by installing handrails, but if workers aren’t in the habit of using them they can still fall down the stairs.

Worse yet, production schedules can “encourage” workers to rush down the stairs and trip over their own feet—and there isn’t a single compliance measure that can eliminate the risk of rushing. The way we manage the workplace can actually create higher risk of error and injury. And unfortunately, many safety professionals prescribe to the notion that OSHA is the only effective way to reduce injuries, which means that our understanding of the problem isn’t clear.

The goal should be the elimination of injuries and reduction of risk, and I’m always disappointed when organizations resist using human factors training to combat at-risk behavior like rushing that cannot be addressed through compliance alone. This type of training looks at eyes on task, mind on task, reasonable speed of work, extended body position, etc., and can even augment regulatory compliance in some cases.

Status Quo Bias

Safety programs that are oriented towards addressing regulations have become the status quo for the safety professional and management in general. In fact, many organizational approaches to safety come from a bias towards the status quo. It’s such a big problem (and not just in safety) that it’s got its own name— status quo bias, which is an emotional preference for the way things currently are that can affect otherwise rational decisionmaking.

Change initiatives represent a path less traveled and by definition are a departure from the status quo. As such, they can potentially open safety professionals up to criticism from management asking, “You want to spend more money on what?!” to employees wondering why they’re being trained on something that isn’t required.

Conversely, sticking with the status quo presents little overt risk in terms of job security or professional reputation. But if the goal is to reduce injuries by as much as possible then it’s clear that the status quo bias must be overcome. If you stick with the status quo then you will only get status quo results.

Risk Perception

Another obstacle to change is an organization’s general approach to the perception of risk. Often, injured employees and their supervisors evaluate the seriousness of an event by the result. For example, an employee with a small cut on their finger might feel frustrated at having to fill out a three-page accident report for what appears to be a minor injury. A sage employee may not even report a similar injury in the future because the reporting process appears to provide little value.

Another obstacle to change is an organization’s general approach to the perception of risk. Often, injured employees and their supervisors evaluate the seriousness of an event by the result. For example, an employee with a small cut on their finger might feel frustrated at having to fill out a three-page accident report for what appears to be a minor injury. A sage employee may not even report a similar injury in the future because the reporting process appears to provide little value.

In this case the employee is evaluating the seriousness of the event based on the injury—the result. However, in the safety profession we evaluate the seriousness of the event by its potential. Making a change in our safety system based on a result like a small cut will meet natural resistance if the potential risk isn’t evident to all stakeholders.

The best way to address problems with perception is through education. Companies have a decent track record of teaching workers the mechanical functions of a change—like the ins and outs of new paperwork or processes—but spend far less time educating employees on the reason a change is necessary. At the outset of any change initiative, companies can secure employee buy-in by clearly explaining why the change is necessary, why it will be beneficial for employees and by answering any questions they have. Doing so will not only recalibrate workers’ risk perception but it will cut down on their resistance to change too.

Not-So-Common Sense

Many people believe safety isn’t difficult and to avoid getting hurt one only needs to pay attention to what they’re doing. I frequently hear safety professionals wondering why they should spend time and money on safety training when the issue is common sense. The unavoidable implication is that less intelligent people get hurt more often.

There are two major issues that get overlooked in the conversation about common sense. The first is that common sense means different things to different people. One person’s life experience might lead them to think that it’s common sense to take a slowand- steady approach at work, whereas another might believe it makes sense to work as fast as humanly possible to show how eager and ambitious they are. In this case it’s up to the safety professionals to help everyone incorporate a safe approach in their common sense.

The second issue is that there’s little correlation between individual intelligence and the ability to maintain a high level of awareness over a long period of time. The former is about natural ability and the latter is about stamina, skills and training to improve endurance. If you want someone to pay attention throughout their shift, you can slowly build up their fortitude (think of it like a runner training their body to cover more distance every week), and you can provide motivation that will help them stay focused when their attention starts to flag. And most importantly, you can give them the skills to fight off the biggest causes of distraction, especially human factors like rushing, frustration, fatigue and complacency.

Conclusion

These four roadblocks are a significant threat to any new safety initiative. To successfully manage any change, start viewing regulatory compliance as one tool among many rather than the only answer. Then add a few more tools, from resisting the status quo bias to adjusting the perception of risk and, finally, to recognizing that safety shouldn’t rely upon common sense. By using the five essential components of organizational change as a roadmap to navigate these roadblocks, you’ll drastically improve the likelihood of safety success.

Gary is an expert in safety management systems and organizational change, he is a two-time past president of the Hawkeye Chapter of the ASSP and past Regional Safety Professional of the Year. In 2010, Gary was awarded the Distinguished Service to Safety Award, the top individual safety award from the NSC.

Get the PDF version

You can download a printable PDF of the article using the button below.