By Gary A. Higbee, EMBA, CSP

How good is your safety program? Twenty years ago, I set out to answer that question by identifying five stages an organization passes through on its way to world class safety performance. I’ve seen a lot in 20 years and I’ve since refined my answer. Here’s what I said back then.

Evaluating Safety Performance

Determining the quality of your safety program is a lot trickier than it might appear. Some people think it’s a numbers game. They think if there aren’t a lot of injuries and illnesses, then the program must be good. If there are a lot of injuries and illnesses, then the program must be bad.

If only things were that simple! Equating the number of accidents and illnesses with the quality of the safety program is confusing cause and effect. It also overlooks the role of luck—good and bad—in workplace safety.

The journey to attaining world class safety performance starts with a clear understanding of:

- Where you have been

- Where you are today, and

- Where you are going if nothing changes.

When you understand these things, you can determine the changes you need to make and the path to take to achieve your goal.

Then—Five Stages of a ‘Good’ Safety Program

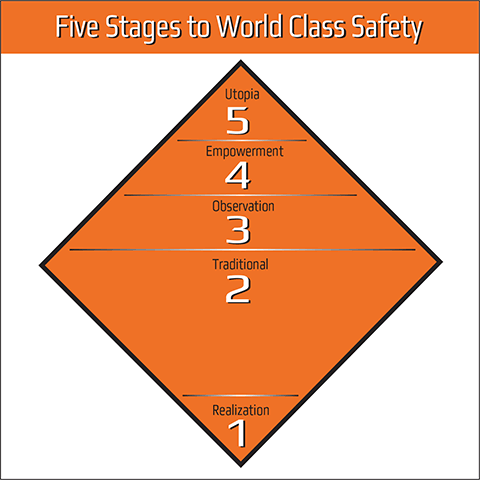

Where is your program right now? There are five stages that organizations pass through. (Some organizations go through a combination of two at the same time):

Stage 1: Realization

This stage is marked by high injury rates and workers’ compensation costs. Employees are at high risk of injury and the company at high risk of liability. The direct costs of lost time injuries eat away at profitability. All of these factors exert pressure on management to “do something.” Audits are conducted to identify areas most in need of improvement.

Stage 2: Traditional

In this stage, companies make it a priority to develop policies and procedures. This is also when the education process begins. As yet, the organization has had no success in changing behaviors. Employees and management continue to do what’s convenient without regard for safety. Steps taken to identify and address hazardous conditions have resulted in higher production and overhead costs. Machine maintenance and repair, shielding and guarding derive from a reactive—“we’ll fix it when it’s broken”—approach by management. Employees are still at high risk of injury but the company’s liability risks have probably been reduced since obvious compliance problems have likely been addressed and workers’ comp precludes employees from suing the company for their injuries.

Stage 3: Observation

During this stage, management initiates an observationbased safety program in addition to the traditional program. Management is driving the improvement process with little to no employee involvement. Managers spend more time on the production floor or the worksite “observing” for hazards. Compliance is at the forefront of their minds and better documentation and recordkeeping are a priority.

Stage 4: Empowerment

Management and employees now share responsibility for assessing risks and preventing injuries. There’s joint accountability in the education process. Employees have gained confidence in the management group and believe that safety is a core value of the organization. Employees drive improvement and are committed to company goals. Injuries fall. Employee observations have increased awareness of risk factors resulting in the development of ‘habit strength’ for effective safe behaviors. The gains made in safety are improving the company’s financial performance. The company has gained a competitive advantage because the decline in lost time injuries has freed up resources for allocation to other parts of the business. Consequently, productivity and quality improve.

Stage 5: Utopia

The company’s safety culture is self-sustaining and developing. Employees are looking out for each other and peer-to-peer safety interventions are a normal part of the operation. The company is progressive in its approach to safety and has become a benchmark by which other companies in the industry measure their own safety performance.

Now—The Weak Link of a Safety Program

Back to the present. As I noted above, I wrote this essay about 20 years ago. I’ve learned a lot since then. While I still believe in the five stages of progression, I now realize that my analysis wasn’t complete. I’ll explain what that missing aspect was when I present my “mature” view of how to access a safety program.

The refinements I mention relate principally to the fourth stage: Empowerment. As you recall, that’s the stage when management and employees share responsibility for risk assessment and injury prevention. This is also the point at which employees have become aware of risk factors and developed “habit strength” for effective safe behaviors.

When I first described this stage, I made a misjudgment about “habit strength.” More precisely, I made an assumption that I now realize is flawed. Under normal situations, habit strength does result in safe behaviors. But what I failed to recognize is that this isn’t always true and that safe habits break down when individuals are under stress.

A Moment of Revelation

This bit of wisdom first struck me when I was performing an audit at a manufacturing facility. I was observing a forklift operator who I knew was particularly good at his craft. He always wore his seatbelt and never set a load at the production line without clearing the employees. When he entered a trailer at the loading dock he always inspected the trailer and assured the wheels were caulked. He just did everything right.

In the afternoon, I noticed some extra activity on the production line. The line was going down because of a missing part that was stored outside in a trailer that was stuck in the snow. The assembly line employees were incentive workers and they didn’t want the line to go down because it would cost them money.

Just 30 seconds before the line was to go down, the truck was freed from the snow and backed to the dock. The same forklift driver that I had admired for his impeccable work and safety habits jumped onto his forklift, drove into the trailer and got the load. He placed the load on the line and everyone cheered.

The problem was he didn’t fasten his seatbelt, the trailer was not caulked and if the truck driver had pulled forward to reset the trailer, who knows what might have happened. The forklift operator’s habit strength was lost in an instant.

My Revised Viewpoint—From 5 Stages to 3 Attributes

This incident gave me pause and caused me to rethink. The many safety programs I have observed over the years have had the same effect. The product of this is a more mature and simplified theory.

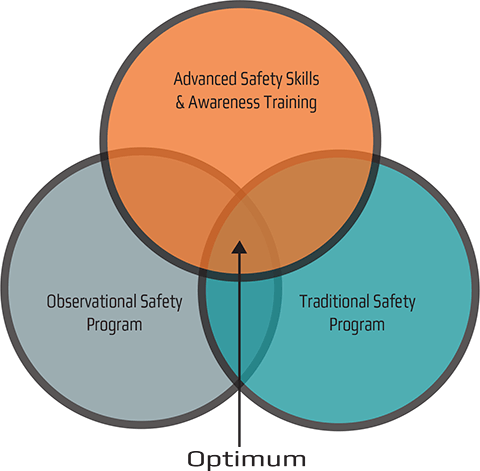

My theory has morphed from five stages to three attributes. In other words, there are three attributes that all world-class safety programs have. Now, I judge the effectiveness of a safety program by determining if it has those attributes:

1. Traditional Safety Program

Yes, I still believe you must have a strong traditional safety program. This includes written programs, policies and procedures and ensuring that these policies and procedures are followed. You can assess your own traditional safety program by auditing them to set standards. You can do this internally or use an outside auditor. It’s a simple way to look at what you say you’re doing and see if you are actually doing it. Most of us have a lot of work to do just to get our traditional programs up to snuff.

2. Observation Programs

This is a combination of the observation and empowerment stages from the five stages theory. Companies with first-rate safety programs have an observation process to watch for at-risk behaviors. It’s not an audit program, but a behavioral observation process that involves both employees and management. There needs to be teamwork.

Workers on the floor are encouraged to perform safety observations on a peer-to-peer basis. They’re also encouraged to accompany the supervisor and safety director on their rounds. What are they looking for? Three things:

- Whether workers know how to do their jobs

- Whether workers have the tools necessary to perform their tasks safely

- Whether there are any gaps in the system.

Workers observed committing at-risk behaviors are not disciplined, but engaged in discussion whose purpose is to correct the observed at-risk behavior.

With an observation program, you’re reinforcing safe behaviors and intervening when at-risk behaviors are observed. This process develops ‘habit strength.’

3. Advanced Training

We wouldn’t expect a person who’s never played golf before to read a golf rulebook and suddenly become a pro. We understand that the person would have to be taught about the game and shown how to play it.

It’s the same with employees. Employees need advanced safety skills and safety awareness training. In order for the traditional and observation programs to be successful, employees must be taught the skills that will keep them safe when the system breaks down. They need practical, relevant and easy-to-understand skills to manage themselves effectively. Without this, the system will continue to fail under stress, because some will lose the habit strength.

This recognition is what was missing from my original five stages theory.

Conclusion

After 20 years, I still believe that world-class safety performance is not just the dream of some wide-eyed college graduate or recently appointed safety manager. It is a very attainable goal. But it takes a commitment to have a strong traditional safety program, an ongoing observation program to catch gaps and advanced safety skills and safety awareness training for all employees.

Gary A. Higbee is a Certified Safety Professional and has an MBA from the University of Iowa. He worked for over 32 years for John Deere & Company where he held assignments in safety, environmental, production and engineering. He has earned numerous awards, including the 2010 Distinguished Service to Safety Award and the Gary Hawk Safety Award. With over 45 years of experience, Gary has become an internationally recognized speaker on safety, health, environmental and business issues.

Get the PDF version

You can download a printable PDF of the article using the button below.